| Collection #: | 2023.001 |

|---|---|

| Type: | Rifle Officer's sword |

| Nationality: | British / Commonwealth |

| Pattern: | 1827/45 Pattern |

| Date: | 1878 - 1880 |

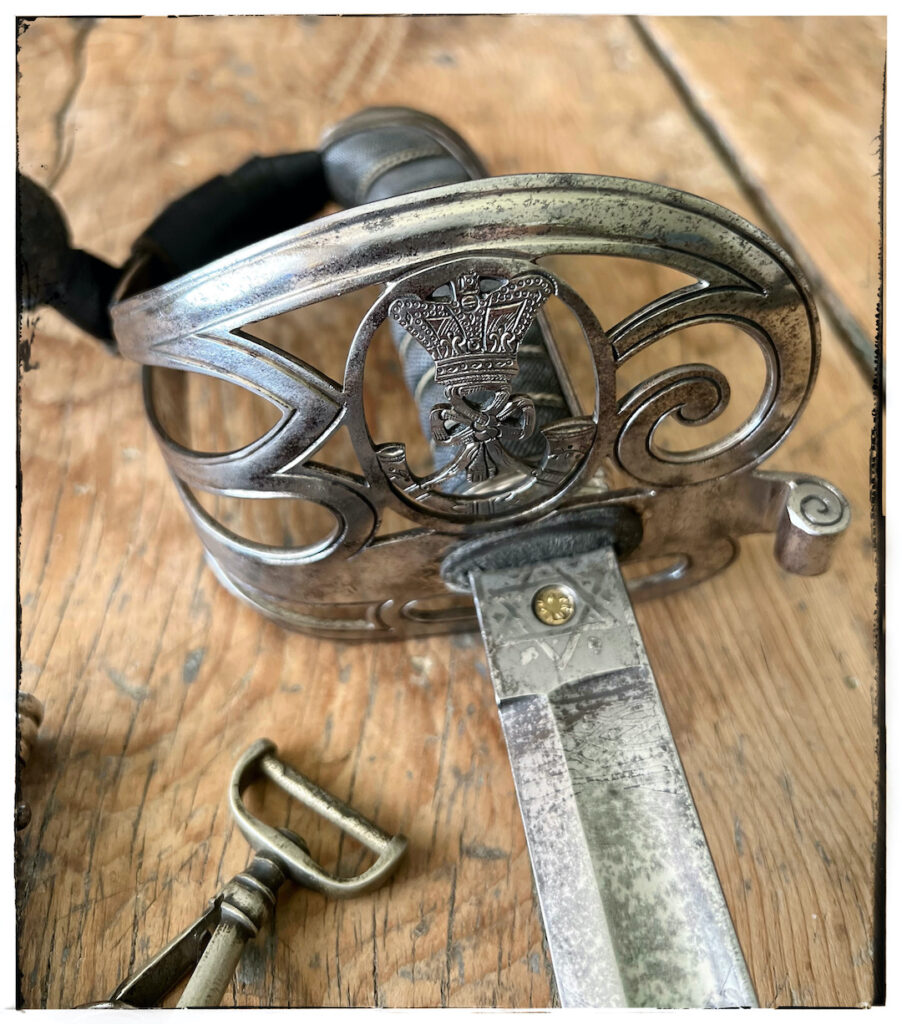

| Hilt: | Half Basket |

| Blade Length: | 83.3cm (32.8") |

| Blade Width: | 2.5cm (.98") |

| Overall Length: | 99.6cm (39.2") |

| Maker: | Maynard, Harris & Co. Leadenhall, London. E.C. |

| Blade Markings: | VR Cypher for Queen Victoria and XCth Winnipeg (strung bugle) Rifles (Beaver) and floral decorations |

British rifle regiments found their origin in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in 1755. However, the rifle brigades that we are familiar with today were mostly formed around 1800.

Officers were initially known to carry a smaller version (shorter blade for use on foot) of the 1796 Pattern light cavalry sword. In 1803, they adopted the newly introduced (although with variations already in use) 1803 Pattern. The version of the 1803 Pattern used by rifle regiments can sometimes be identified by the added detail of a strung bugle over the GR royal cypher on the knuckle guard. Why a strung bugle? The implementation of the bugle was used to control troop movements in rifle/light infantry regiments as opposed to the drum that was used by regular infantry of the line. (Withers, 2010)

Prior to the adoption of the 1827 Pattern (1820 – 1827), rifle regiments were to use the infantry’s 1822 Pattern with a steel scabbard for undress (in the field) and a black leather scabbard for full dress and evenings.

Known for their elite individuality in both uniform and tactics, rifle regiments were not pleased about using the same sword as the rest of the infantry. They wanted their own sword. A memorandum in 1827 authorised rifle regiments to carry a steel hilted (as opposed to the brass hilt of the regular infantry) sword of Gothic pattern with the royal cypher in the guard replaced with a crown over a strung bugle. It should be noted that there are some examples where regiments have used their own regimental badges in the guard instead of the strung bugle. These are sometimes referred to as the 1854 Pattern.

In 1845 a new style of blade was introduced by the Wilkinson Sword Company. The new blade style removed the pipe back, added a single fuller along the length of the blade for strengthening. The new style also had a lengthened forte, adding a brass proof slug to guarantee authenticity as a Wilkinson blade. The practice of adding the brass proof slug was quickly adopted by other blade manufacturers as well. The new blade was considerably stronger and a better all-around fighting blade. (Robson, page 159)

Examples are still relatively common as this pattern is still used in the British Army and throughout Commonwealth countries that continue to follow in the tradition of using British patterns.

Summarised from the 90th Winnipeg Rifles Museum at the Minto Armouries in Winnipeg, Manitoba

Winnipeg was viewed as the farthest outpost of civilization on the western plains. The decision was made that a rifle regiment, trained in independent firing, open-order skirmishing and rapid deployment, while working without the support from other units, was best suited for western service. Thus was born the 90th Winnipeg Battalion of Rifles in 1883.

– 90th Winnipeg Rifles Museum

In 1883, the Government of Canada approved the formation of the 90th Winnipeg Battalion of Rifles. William Nassau Kennedy was to be their first Lieutenant-Colonel. He was a veteran of the Red River Battalion and former Commander of the Winnipeg Volunteer Infantry Company during the Fenian Raids.

In 1884, twenty-five officers and men from the 90th Rifles were utilised to transport troops and supplies up the Nile River to relieve the besieged men at Khartoum in the Sudan. Unfortunately, by the time they arrived, the garrison had already fallen.

1885, and there was growing economic discontent (1883 – 1884) in what was then the “North-West Territories” (at this time comprising Alberta and Saskatchewan). Louis Riel formed a provisional government at Batoche, Saskatchewan in opposition to the Canadian Government.

The 90th Winnipeg Rifles were sent out on a winter march towards Batoche. They had their first encounter when they were ambushed by Metis fighters at Fish Creek. They held their ground but lost six men. Their next engagement was at Batoche on May 9th. Four days later the rebellion was quelled and its leaders were captured.

In quelling the rebellion, the 90th Rifles received the nickname “Little Black Devils”.

By the 1870s, there were 12,000 people living in Manitoba. Three thousand of them were living in Winnipeg. With the advent of the railway, by the late 1880s, the population of Manitoba had grown to 60,000 and Winnipeg was now the largest city in the West with a population of 26,000. With a growing population, the Red River Rebellion in 1869 and the Fenian Raids in 1871, evidence in support of a protective force continued to grow.

By the 1870s, there were 12,000 people living in Manitoba. Three thousand of them were living in Winnipeg. With the advent of the railway, by the late 1880s, the population of Manitoba had grown to 60,000 and Winnipeg was now the largest city in the West with a population of 26,000. With a growing population, the Red River Rebellion in 1869 and the Fenian Raids in 1871, evidence in support of a protective force continued to grow.

Kind of like Schrödinger’s cat, I like to think of this as Schrödinger’s sword. In the picture above you can see William Nassau Kennedy holding an 1827 Pattern Rifle Officer’s sword, and if you zoom in you can see the same Star of David (or Damascus Star, depending on what research you follow) as on the example here. However, that star is still relatively common on officers’ swords of this era. The location of Nassau’s sword (to my knowledge) is unknown. Therefore, while you cannot say for sure that it is his sword, neither can you say it isn’t. How many swords (which were mostly ceremonial at this point) would there have been in the regiment at its beginning? How many would have been engraved with the XCth Winnipeg Rifles?

To learn more about the 90th Winnipeg Rifles, visit the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum & Archives located inside the Minto Armoury in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

A Victorian example of the Rifle Officer’s pattern in use since 1827. The 1827 Pattern is still used by rifle regiments. This example is in quite good condition. There is some darkening of the metal near the back of the backstrap of the grip and on the tang button and minor spotting on the blade. The Sharkskin grip has not suffered any losses. The main wire (steel or silver) around the grip is tight with the secondary (smaller) wire having some minor wiggle. The gothic-themed, nickel-plated guard is tight with no movement.

The sword knot, while correct for the sword, is not original to this particular sword.

The blade still retains a mirror finish with spotty darkening of the metal. There are only minor nicks towards the end. The right side of the blade has a brass-proof slug which has stamped into it (in a semi-circle) PROVED and a P at the bottom. This is followed by floral decorations then a beaver (often a symbol on Canadian swords). Above the beaver is a strung bugle surmounted above it with XCth Winnipeg and below it Rifles. The left side of the blade lists the maker, then floral displays. This is followed by VR (Queen Victoria) royal cypher surmounted by a crown, then more floral displays to finish the etching.

Read the full accounts of what these authors have recorded, plus some other research or references on this pattern:

Robson, B. (2011) Swords of the british army: the regulation patterns 1788 to 1914 (Revised Edition). The Naval & Military Press, Uckfield, East Sussex, England. Pages 159 & 160.

Withers, H. (2006) World swords 1400-1945 – an illustrated price guide for collectors. Studio Jupiter Military Publishing, Sutton Coldfield, UK. Page 174.

Withers, H. (2008) An illustrated encyclopedia of swords and sabres. Anness Publishing, London, UK. Page 197.

Withers, H. (2010) British military swords: 1786-1912 the regulation patterns. Harvey Withers Military Publishing, Sutton Coldfield, UK. Pages 28, 33 & 35.

For further visual research, feel free to look up the following books for photos of other examples of this sword.

Dufty A.R. (1974) – European swords and daggers in the tower of london. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London, UK. Plate 77c

Robson, B. (2011) Swords of the british army: the regulation patterns 1788 to 1914 (Revised Edition). The Naval & Military Press, Uckfield, East Sussex, England. Page 160.

Withers, H. (2008) An illustrated encyclopedia of swords and sabres. Anness Publishing, London, UK. Page 197.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies. Enjoy the cookies...they're delicious...

Websites store cookies to enhance functionality and personalise your experience. You can manage your preferences, but blocking some cookies may impact site performance and services.

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us understand how visitors use our website.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool that tracks and analyzes website traffic for informed marketing decisions.

Service URL: policies.google.com (opens in a new window)