By Matthew Honey

Since the beginning of the European settlement of North America, it has been a catch-all of outdated military arms used throughout Europe. They were brought by explorers, refugees or as cast-off items no longer in sync with current military styles. Influenced by social and national trends, swords were always evolving – adding to their diversity. Some edged weapons were developed with specific jobs in mind. Out of necessity, some were put back into service. Others were repaired or modified to keep in step with changing fashion. In the end, without standardization, the result is a vast conglomeration of varying sword designs, sometimes with unclear original purposes (aside from the obvious).

R.B. Manarey (1970) gives us a snapshot of early weaponry in his book, The Canadian Bayonet. The information predates our time frame a little but does give a good picture as to why there is such a wide variety of pieces to be found in the early years of settlement of North America. He records that “the Company of One Hundred Associates, known officially as The Company of New France, was the governing body of Canada from 1627 to 1663. In the middle of their tenure, their Governor ordered a dictum stating that the inhabitants of the New World were to arm themselves at their own expense and form a militia. The natural result of this order was that each individual purchased arms according to his financial capabilities and his own taste. Thus a great variety of weapons began to appear in this virgin land…” (p. 1).

French settlement in Canada would gradually come into a wider and wider conflict with English settlement until the matter was finally settled with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. English settlers would now move in and establish their militias, thus again introducing new styles of edged weapons among the general population. An example of this was the first militia act in New Brunswick passed in 1787 where “each militiaman had to provide his own weapon, either a musket or fusee, a good bayonet, a cartridge box, nine cartridges of gunpowder and three bullets” (Facey-Crowther, 1990, p.7). By 1787, the use of the sword by the regular soldier had been mostly abolished, having been replaced by the bayonet. Mounted soldiers still used the sword and officers were still required to purchase their own swords as suited to their preference and style.

Faced with a large diversity and date range of swords, the historian needs a way to be able to date these pre-regulation slivers of history. As for regulation swords, their dates of activity and manufacture are known because their description has been written out in General Orders. So how does one know if an existing pre-regulation sword is from the 1600s and still in use? How can a researcher tell what country a particular style of hilt stems from? This is a divergent topic from the intent of this article, but in brief, the following methods can be useful. One way of attempting to place a sword within a time frame and identify it as belonging to a certain nation is the use of paintings where the date of the artist is known. An officer in a portrait may be done by a known artist for whom we know their date of activity. The officer himself may be known by name or have a recognizable uniform, which can also help to date a sword and also place it within a military branch. However, this method is not foolproof as men would sometimes be painted with their grandfather’s sword or the fanciest sword they could find. Outside of this method, or the sword actually having a date on the blade, it has been extremely difficult to identify common styles and place them within a specific period of time for pre-regulation swords(Newman, 1973).

However, standardization was just around the corner. It is with the unauthorized conflict (the colonial uprising known as the American Revolution) in North America that the gradual formalization of the sword into recognizable patterns starts to become visibly apparent on this side of the Atlantic. While formalization primarily took place in England, its results were reflected in Canada and even the United States. From 1750 to 1814, North America would see three major conflicts where the sword played a role. The Seven Year’s War between England and France pitted country versus country. The American Revolution saw civil unrest grow, the population rise against their own nation to obtain independence, and finally, in 1812, nation versus newly formed nation (Cross, 1984).

Each of these conflicts brings to light a glimpse into the gradual formalization of swords (within the British sphere, the French having formalized a little earlier) into official patterns. Peterson (1968) records that in the Seven Years’ War and leading up to the American Revolution, there were accepted styles or common designs employed by the warring nations, but not made official or universal. While Newman (1973) states that the American Revolution saw the general population bring into use a chaotic variety of swords that had been brought to North America (fig. 2). Finally, in the War of 1812, formalized sword patterns, established in England, began to make an appearance. Infantry, cavalry, navy and artillery all began to have recognizable types, as prescribed in General Orders, that distinguished one military branch from another. British North America and the United States would even briefly be mostly uniformed in their designs for a period.

On a continent settled by people of numerous nationalities, a resulting variety of sword designs are to be expected. Smallswords, hangers, cutlasses, sabres and hunting swords or cuttoes are just a few of the types found. Each had its own nationalistic style of hilt (the section comprising the handle, guard and pommel). Couple this with domestically produced, imported, modified and heirloom blades and the variety increases exponentially (Newman, 1973).

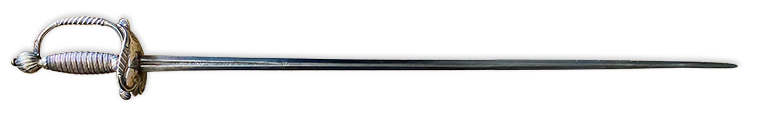

George Stone (1961) describes the smallsword as “the last form of the rapier. It usually has a triangular blade which can only be used for thrusting and the advantage of which consists in its lightness. The hilt is simple, the guard consisting of an elliptical plate or two shells, and a light finger guard” (p. 568). It is typically identified by its long narrow blade and fine delicate hilt. Hilts could be of steel, brass or silver. Blades also came in a variety of styles, but the key repeated feature was that it was long and slender, intended for piercing, not slashing. These swords were typically associated with civilian use from c.1650 until c.1750 (Norman, 1980).

From 1750 until 1780, the range of hilt designs increased and common patterns by hilt makers became apparent as more officers chose to carry them. Besides their fanciful and delicate designs, the smallsword played another role in society. It also represented a man’s social status. According to Newman (1973), gentlemen carried this style as part of their everyday wardrobe as well as for military ceremonial purposes, and the nicer the sword, the higher his social ranking. He only relinquished it to safe keeping when he went into battle, at which point he took up his sabre.

The Sabre is defined by Stone (1961) as “a sword with a single-edged, slightly curved blade, usually with a short back edge. It is intended for cutting, but is also effective for thrusting” (p. 530). The sabre often came in two different lengths. The short sabre, typically carried by infantry officers on foot and used as a slashing weapon, was normally used on the battlefield instead of their smallsword. The length of the blade was usually less than 32 inches (Newman, 1973). The sabre was not always as elegant as the smallsword, but more battle-worthy.

The length of a horseman’s sabre typically started at 32 inches and increased from there. In the hand of a horseman, it was possibly the most devastating weapon on the battlefield. Neither the musket nor the pistol could stand in the face of a mounted charge (Peterson, 1968). Colonels of cavalry regiments were often provided funds to secure swords (among other equipment) for their men. Some officers purchased high-quality swords for their men and other less scrupulous officers purchased the cheapest arms they could find and kept the remaining money for themselves. Further complicating the situation was that a large variety of sabre styles were in use and the ability to uniformly replace broken swords was difficult (Robson, 2011). Some say that variety is the spice of life, but in these circumstances, it is a spice that created a major headache when a regiment was on a different continent than its supplier.

Something had to be done. Infantry officers were flip-flopping between one sword for ceremonial use and another to wear in the field. Cavalry units were each choosing their own style of sabre, and not all of those styles were necessarily of good quality. Muskets had already been standardized some time ago to make the replacement of parts easier, but not swords (Robson, 2011). On top of this, colonial militia units were bringing into use whatever swords they could get their hands on. In a newly developing continent, many of the swords are already ancient and outmoded designs being modified for use during their working life in North America (Withers, 2006). This is where the government began to step in and provide some control over the style and quality of arms being purchased.

In 1786/88, the British government requested that regiments send them an example of the style of sword being used in their regiment. The intent was to try to set some standards so that all regiments would be purchasing and using roughly, the same style of sword. Also, the quality of construction could be verified. Blades would now be inspected and a crown with a number (referring to the inspector) would be stamped on the blade if it passed inspection. This resulted in standardization or “patterns”.

General Orders were given specifying regulations to be followed. Thus swords constructed before 1786 are often referred to as pre-regulation. After 1786, most military swords fit a regulation pattern. If a military sword does not fit a regulation pattern and is post-1786, it is often referred to as a private purchase (custom ordered) for an officer. Probably 90% of military swords will fit into one of these three general categories. The next step would be to determine if a sword is military-related or intended for civilian use.

Back to our first attempt at regulation. The first round affected the blade design only. Its width and its length would be uniform. There was little discussion regarding the hilt at this time. Colonels would still purchase their swords from their preferred supplier. Some standardization was now in place, but not fully developed. The resulting patterns that stemmed from this were the 1786 pattern for the infantry (fig. 7) and the 1788 pattern for the light (fig. 8) and heavy cavalry. Revolutionary War in France would bring the next wave of troubles as merchant supplies were slowly cut off (Robson, 2011).

Meanwhile in British North America, Great Britain had recently concluded the American Revolutionary War. Loyalists were settling in Upper and Lower Canada and the maritime provinces. They were still using whatever swords they had available to them at the commencement of the war. Rene Chartrand (2011) records that Canada relied heavily on the British arms industry. The war with France, however, meant England had other priorities, which resulted in Canada having an extreme shortage of both muskets and swords. A dangerous position to be in as the other half of North America (the United States) had actively begun their own sword manufacturing industries.

With an increase in skilled immigrants to the United States, domestic production of goods (including swords) was increasing. By 1801, Virginia had already constructed its own arms manufactory (see figure 12, top sword for a sample produced here). Tensions between England and the United States had already nearly ignited a war in 1807. It was at this key point that the Americans had begun to truly focus on building up their supply of arms (Bezdek, 1997).

The year 1796 brought further standardization and the first General Orders to describe the blade and hilt. This applied to both the infantry and cavalry swords in use at the time. The infantry pattern 1796 sword (fig. 9) was an evolution of the 1786 pattern which had evolved from the smallswords carried earlier in North America. The blade had been regulated in 1786 to be 32 inches long and 1 inch wide at the shoulder (top of the blade where it meets the hilt). The hilt had not been regulated and there were three common types in circulation. This time the hilt design was cemented. It was to be of a double shell guard, one side able to fold down flat, with Adam’s urn pommel and either silver twist-wire or silver sheet to cover the wooden core of the handle. Not the most robust of swords, but designed for an era when looks were more important than function. This pattern of sword introduced in 1796 would continue in service until 1822 at which time the pattern would evolve again. This general style would also influence American sword patterns into the 1840s (Withers, 2006).

The cavalry sword was also updated. The new specifications were to be called the 1796 pattern light cavalry sabre (fig. 10) and the 1796 pattern heavy cavalry sword. Officers often purchased their own more elaborate examples. In 1788, specifications for this cavalry pattern mostly described the blade length, width and curvature (in the case of the light cavalry), and a minimal hilt description. As blades were made both domestically and imported, there was still some slight variation. Interestingly, Robson (2011) states that sourcing and purchasing of regimental swords was still in the hands of their colonel, while Richard Dellar says, “those swords were to be sourced by the Board of Ordnance rather than the individual colonels of each regiment” (Deller, 2013, p. 5). Either way, it all changed in 1796, including a new design.

Unlike the infantry pattern that was simply expanded upon, the cavalry pattern received a complete overhaul. The proposed new style was based on recommendations made by Major J. G. Le Marchant, who had devoted a large portion of his time to analyzing the best design for the cavalry sword. His design recommendation was accepted for the light cavalry pattern (Robson, 2011). The knuckleguard style of the 1796 pattern was updated with the new P-style guard from the older D guard. Blade dimensions were kept relatively similar but the width of the blade widened as it approached the end before quickly coming to a hatchet tip. The thought behind this was that it added weight to the tip of the blade, which would increase its chopping power (Deller, 2013). This has become possibly one of the most recognizable of all British swords. The 1796 pattern heavy cavalry sword would be based on the “Austrian heavy cavalry sword, the Pallasche fur Kurassiere, Dragoner und Chevaux-Legers, Model 1775 (Robson, 2011, p.18) and popularized in the Napoleanic military tv drama, Sharpe’s Rifles.

Further development came after 1800 when flank companies of infantry regiments (light infantry and grenadiers) also adopted a pattern of sabre. This was titled the 1803 pattern flank officer’s sword (fig. 11). The 1803 pattern sabre had a similar blade to the cavalry, but shorter. The guard was of gilt brass with a lion’s head pommel and King George III’s royal cypher moulded into the knuckle guard. It has also been described as possibly one of the most beautiful and collectable of all British swords (Withers, 2010). Two other rarer examples of this sword exist. In place of King George’s cypher (or above it), one example has a strung bugle for light infantry and the other example has a flaming grenade for grenadiers.

The 1796 pattern infantry and cavalry swords and the 1803 pattern were all present and in use in North America throughout the War of 1812. Though supplies were low initially, Sir George Prevost worked diligently to increase supplies as tensions rose with the United States (Chartrand, 2011). The United States had an ever-growing, domestically manufactured, supply of arms. It is interesting to observe the design of their artillery and cavalry swords. They were virtually identical to that of the British 1796 pattern light cavalry sword (fig. 12). The American infantry sword also reflected the design of the earlier British 1786 pattern infantry sword; thus, through conflict, a sense of uniformity developed across all of North America, even if only temporarily.

This is a very general overview of the evolution and standardization of British swords (and to some degree American), in North America. North America had its unique challenges which resulted in a large variety of designs and styles of swords. With no large formal military presence, civilians formed militias and used what they either had or could afford. Some swords are defined by their intended purpose of either hunting, social or military usage. Some are simply defined by the nationality of settlers who came to this country and brought them from their homeland. One thing was for certain, they were not of a uniform design. With the standardization of regulation patterns by the early 19th century and the introduction of larger military forces on the continent, we see the trickle down of those official patterns from England and its creep into American sword production.

Inside the official armies of the warring nations such as France and England (early to mid-1700s), some uniformity could be found, but it was not always consistent, nor was it official. The rise of the American Revolution brought to the surface the wide variety of swords in existence as citizens resorted to whatever arms they could find to arm themselves. There are so many styles of pieces used during the revolution that there are 300-page books written that are filled with images of edged weapons known, or thought to have been used during the conflict. However, almost another 30 years later, the War of 1812 reared its head and now there was a much smaller range of designs employed and a sense of uniformity within different military branches and even amongst nations.

Moving into the future, this uniformity will continue to persist. It will be influenced by advancements in manufacturing and political alliances. In the lower half of North America, the United States will initially base their domestically produced swords on British patterns. However, after the War of 1812, the design influence will become distinctively French until around 1900 when they will finally diverge into their own original designs.

In British North America, Canadian military-issued swords will continue to evolve right up to the present day using the identical patterns (with the odd exception) issued to the British forces. The early European settlement of North America had introduced a wide variety of styles of blades and hilts to the military establishment on the continent. However, by the early part of the 19th century, uniformity was well underway in the ongoing development of the sword in North America.

Bezdek, R. H. (1997). Swords and sword makers of the war of 1812. Boulder, Colorado: Paladin Press.

Chartrand, R. (2012). A scarlet coat: Uniforms, flags and equipment of the British forces in the War of 1812. Ottawa, ON: Service Publications.

Dellar, R. (2013). The british cavalry sword, 1788-1912: Some new perspectives. United Kingdom: The Choir Press.

Facey-Crowther, D. (1990). The new brunswick militia, 1787-1867. New Brunswick: New Brunswick Historical Society and New Ireland Press.

Manarey, R. B. (1971). The canadian bayonet. Edmonton, AB: Century Press.

Neumann, G. C. (1976). Swords & blades of the american revolution. Harrisburg, PA: Promontory Press.

Norman, A. V. (1980). The rapier and small-sword, 1460-1820. London, UK: Arms and Armour Press.

Peterson, H. L. (1968). The book of the Continental soldier. Harrisburg, PA: Promontory Press.

Robson, B. (2011). Swords of the british army: The regulation patterns, 1788-1914. London, UK: The Naval & Military Press and National Army Museum.

Stone, G. C. (1961). A glossary of the construction, decoration and use of arms and armor in all countries and in all times; together with some closely related subjects. Jack Brussel Publishing.

Webster, D. B. Cross, M. S., & Szylinger, I. (1984). Georgian canada: conflict and culture: 1745-1820. Toronto, ON: Royal Ontario Museum.

Withers, H. J. (2006). British military swords 1786-1912: The regulation patterns; an illustrated price guide for collectors. Sutton Coldfield, UK: Sutton Jupiter Military Publishing.

Withers, H. J. S. (2003). British military swords 1786-1912: The regulation patterns; an illustrated price guide for collectors. Sutton Coldfield, UK: Sutton Jupiter Military Publishing.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies. Enjoy the cookies...they're delicious...

Websites store cookies to enhance functionality and personalise your experience. You can manage your preferences, but blocking some cookies may impact site performance and services.

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us understand how visitors use our website.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool that tracks and analyzes website traffic for informed marketing decisions.

Service URL: policies.google.com (opens in a new window)